| MESCELLANY |

YEAR: 1910

BOOKMAKING IN NEW ZEALAND

The course bookmakers in New Zealand called "Two to one bar one!" for the last time legally at the Takapuna Jockey Club's meeting in 1910. After the last race they joined hands and sang the popular song of the day, "We Parted on the Shore" (as the Takapuna meeting was always known as the 'Shore').

From that date we saw the once outlawed tote (men had been imprisoned before this for operating a tote at Ellerslie) take the place of the bookmaker who by a turnabout process had become illegal and the tote legal. The bookmakers went underground, not too deeply, and the tote gained a monopoly of legal betting on all racecourses in the Dominion.

There were sporadic prosecutions of the bookmaker. At this period they were not organised into the body afterwards known as the Dominion Sportsmen's Association. They relied on private field agents to wire or phone results and dividends per code as it was also illegal to transmit telegrams connected with betting. The bookies' results were known before the newspapers as it was not until the next day that full details and results would appear in the papers (late results at times would be posted in the window of the newpaper office).

As racing became progressively better organised, side shows and thimble and pea operators were removed from the courses - as were the bookmakers who had an agreement in regard to starting-price bookmaking. They set up limits and modes of betting. For example, when a punter had an all-up wager he would be allowed only three times the original wager on his second choice with one all-up wager being permitted. Thus, if a punter backed a winner which paid £5 and instructed that his bet was to be all up on the second horse, he would have only £3 on his second choice.

In the early days of the illegal bookies, limits as low as even money were bet on entries from certain stables. Limits for country meetings were £3/10/- and for metropolitan meetings £7/10/-.

For a condiserable time a small minority had a virtual monopoly of the S.P. bookmaking business. Those were the days of single pool when there were only two dividends. It was not uncommon for a horse that had been heavily backed to run second and pay as little as seven or eight shillings for the pound invested, and the bookies would make a handsome profit notwithstanding the horse was narrowly beaten. There was a firm of bookmakers operating in Wellington who considered they were having a bad time if they did not keep at least half of the huge cash turnover which passed over the counter of the fruit shop they were conducting in the busy part of the city.

Things went along very smoothly for a long time - the punter was provided with a medium of betting off-course and the books with a cosy income. It was well known that the big time operators had an agent posted near the courses for the purpose of laying off any surplus commitments and that the clubs apparently were prepared to let the bookies proceed along the even tenor of their ways.

The reason given for the tight limits (according to the books) was that it counteracted any move by sharp-shooting trainers or jockeys to let the public with their hard-earned money create the tote favourite while the 'heads' backed the only trier off the course, as their money would not affect the tote price. It was a point, but the real reason would lay in their desire to protect their own pockets. It is true the man in the street, with only form to guide him, would not be in the know of the 'stew pots' - as a race with the favourite 'dead' and few if any triers - was known. He had, it was argued, recourse to the tote if he felt he could find a winner likely to pay over the bookies' limit.

As time went on the ranks of the bookies became swollen. To woo the trade from established operators, the newcomers offered better limits with the result that the oldtimers had to fall into line and do likewise. It was then that the Dominion Sportsmen's Association (commonly known as the Bookmakers' Association) was formed. It was like a huge octopus with its tentacles reaching into every nook and cranny of the country.

Everyone who was in business as an S.P. bookmaker was invited to be a member of the D.S.A. few acted independently as their unity was strength and their ramifications many and varied. They had agents at all meetings and phones installed (in some instances) in private homes near the race track. The householder would have free use of the phone between meetings on condition that on race days it was made available to the field agent, who would be equipped with telescope and glasses to enable him to pick up the result and dividend from the back of the course.

As the race started he would have open a trunk line which would be held by an assistant until the result and dividend were posted. These would then be phoned into headquarters. By these means the result would be relayed and known throughout the Dominion within a very short space of time. Indeed, at times, a punter in Wellington would know the dividend before the people on the course, say, at Auckland. Such was the thorough organisation of the D.S.A.

The membership fees for the D.S.A. varied in different areas, but in all there was a surplus charge (in the vicinity of £1/10/- per quarter) known as the propaganda fund. Whatever that was, one was only supposed to guess. It seemed to be a carefully guarded and well-kept secret. There was no conclusive evidence, but it did seem a coincidence that more non-members appeared to be prosecuted than members!

These conditions continued for some years, each area framing its own rules and limits. The idea of universal rules and limits did not hold as it was found that operators in areas where low limits prevailed could underwrite their business in an area where a higher limit prevailed. A book would often lay the winner that had paid the £20 limit in another area and pay the £10 limit prevailing in his own area. He would gain the reputation of a good loser and prompt payer. Why shouldn't he? He showed a clear profit of £10 on every £1 invested against the punter's nine and had not invested a penny of his own money!

As the profession became more crowded operators became more enterprising, offering as much as ten per cent commission to agents and others who were interested. This was the first nail in the coffin of the bookie, as from this practice grew the 'com' man - an individual who would undertake and successfully place large off-course wagers. He would have sub-agents in all centres throughout the Dominion who in turn placed it with local bookies' agents who were more interested in the commission than in the profits of their principals.

The fact that these large sums could be placed (due to the commission paid) left an opening for sinister activities. When a horse was 'commed' it usually won in spite of having (at times) no recent form. These large wages were so skilfully placed that the money would not get back on the tote and reduce the price.

Another evil connected with this type of off-course wagering was the 'plugging' of the tote - a method of placing a large sum on a 'no-hoper' on the tote and then placing larger sums on the favourite or some horse selected to win or (as it was at times suspected) arranged to win and receiving abnormal dividends which would be collected off the bookies. The Malacca case at Hastings was a case in point. Here, however, the public received a benefit as they received four times the price off the favourite than if the tote had not been 'plugged'.

The galaxy of double charts that appeared in the late forties seemed to indicate that the whole population of the Dominion had gone into the bookmaking business. There were pink ones, blue ones, white ones, green one and ones with all kinds of signs peculiar to the operator. There was no great difference in the prices offering on each - a master chart would more or less set the main. About this time an enterprising individual from the south invaded the Capital City and began printing double charts with astronomical odds. However, he was careful not to bet any fancy prices about horses with a chance of winning. Whereas the oldtimers were prepared to conduct their business quietly and keep prices on their charts sufficiently reasonable to draw business from their patrons.

With the southerner it was a common occurrence to be told that the price had fallen in some double. He had a little over market odds. His thousands to one on this charts were a snare for the inexperienced punter. Anyone with the slightest knowledge of racing would know that the odds on these 'no-hope' combinations should be millions to one. However, it had the desired effect of parting the unwary from their money and creating the illusion that he was giving better prices than the other bookies. With an energy that was commendable this bookie established a business in the Capital on a scale never before seen. He would take all the 'smart' money offering and load it on to the other operators through their agents and per his own agents for that purpose.

It was becoming more apparent that the indiscriminate paying of commission was driving the nail further into the bookies' coffin as their own agents were more interested in the two shillings or one and six in the pound 'com' than their principals' interest. This 'smart' money rarely missed and there was a good deal of suspicion about the results of these confidently placed wagers. The instructions at the source of these (at times) huge 'coms' would be 'no limit' indicating that the result was a foregone conclusion. The 'trot' enjoyed by the responsible group pointed that way at this period.

The above is what is referred to as 'smart' money and the type of business that this southern bookmaker unloaded, plus a considerable portion of his own (to field the losers and back the winner), could only result in an outcome pleasant only for himself. He continued to go from strength to strength and it was an open secret that he was the actual owner of some well-known performers. At this time quite a few loud-mouthed individuals had joined the ranks of racecourse owners (at least they figured in the race book as the owners, their only qualification a lucky chance of no criminal convictions which would have debarred them).

Conference was forced to bring in new rules concerning the deregistering of horses whom it suspected were owned by other than the listed owner. This position more or less continued up to the time of the Royal Commission on Gaming. There was then an opposition association in the north which did not describe itself as an association. It was headed by an ex-executive of the D.S.A. who knew all the inner workings and top secrets of the older body and that perhaps is where its protection lay - otherwise it would soon have been out of business.

The function of the new body was to supply prices to an illegal profession and it did not claim any other distinction. It did not have the efrontery of the D.S.A. to make its case to the Royal Commission on Gambling and supply its arch-enemies, the racing authorities, with figures and facts relating to its ramifications. It was an excellent target for the best legal brains in the country who were engaged by the racing interests to plead their case.

There would be no doubt that the bookies were sanquine enough to believe they still would have control of off-course betting. But the Commission conducted a sort of gallup poll which clearly indicated the public's desire for other means of placing their bets on horse races and the Royal Commission's finding that off-course betting should be legalised (but as directed by the Racing and Trotting Conferences) left the bookies dangling in the air so to speak.

The Auckland headquarters of the D.S.A. were raided by the police shortly after this and it was apparent that this was a case of again 'parting on the shore.' The D.S.A. went out of existence but the operators still carried on getting their dividends wherever they could. By an irony of fate they often got them from the opposition organisation which they had previously looked upon with scorn. The opposition organisation was still in business as it did not have the temerity to appear before the Commission, rightly surmising that it was an illegal organisation and that it would be imprudent to supply the police or the racing bodies with information as had the D.S.A. - such as the fact that its operators were handling £27,000,000 of illegal business per annum. These figures were open to query, but it was good ammunition for the bookies' opponents. This vast sum was the main factor that weighed against them in the summing up of the evidence by the Royal Commission on Gaming. The fact that an illegal body of men had conducted an illegal business and handled such a sum could not favourably impress the Commission. The broadcasting of dividends was also instrumental in putting this organisation out of business.

The position now in New Zealand is that if one wants to make a bet off-course legally, it has to be done per a mechanical monster known as the TAB, a monster which must in time devour itself. The personal contact of the bookies is missing. It would be difficult to imagine someone ringing up the TAB and placing a bet on a horse and telling them that if the horse should lose they will have to wait a while for the money as the income tax was due or the grocer or butcher had to be paid.

This sometimes happened with the bookie who did not mind as the bet was not recoverable by law anyway. Besides, the customer usually paid and everyone was happy. The bookie is still offering this service and also the convenience of not having to make the bet until the last minute from the comfort of the armchair by the radio plus the convenience of not having to deposit the money first.

The bookie is now supplied with his 'divvys' by an obliging radio service, dispensing with association fees and toll bills. It also saves him the extra work of suppling his customers with the prices as they also receive these over the air. The public will alway patronise the bookie, no matter what steps an optimistic police or racing interests take. The continual stream of letters to the press clearly indicates the public's feelings and the bookie will stay in business.

Whatever the outcomeof the all-out drive against the bookie, the man in the street will still have a flutter with the bookmaker!

Credit: 'Reflector' writing in NZ Hoof Beats Oct 1953

YEAR: 1880

It seems that New Zealand's first trotting races were held as part of the programme of some of the galloping meetings in the Otago Southland area as early as 1864.

In his book "A Salute to Trotting" Ron Bisman notes that:-

"The steeds in these events were utility horses in the true sense, almost all of them being driven miles over rough roads and bridle paths to the meetings at which they raced. Ridden in saddle they were all straight-out trotters, tracing generally to thoroughbred blood, which no doubt accounted for their stamina. The times recorded were slow, but the conditions were quite different from today, with tracks so rough and uneven in most cases that pacers would not have been able to handle them and harness racing would have been quite impossible. The horses were totally untrained for racing - most of them sheperd's hacks who did their daily work on undulating or steep country.

Yet these beasts provided interesting contests and laid the foundations of the sophisticated harness racing that we know today. Most of their races were run over three miles, and the minimum weight carried was 11 stone".

The first totalisators were introduced about this time. They faced opposition from a curious alliance of bookmakers and anti-gambling factions but were approved by the Clubs and licensed by the Colonial Secretary.

The first trotting race on a racecourse in Canterbury was held at a location called Brown's Paddock in Ferry Road, Woolston. Contested in 1875, before the totalisator was introduced, the stake was only about a "tenner", but the match created a lot of interest.

About 1880, Lower Heathcote Racing Club was founded, and held its first meetings nearly opposite Brown's Paddock. The club supported gallops, but added trotting events to it's programme, giving smaller stakes.

Some years later the club discontinued gallops and became the Lower Heathcote Trotting Club, which gave stakes ranging from £15 to £35.

YEAR: 1890

|

...Shut the tote - They're coming down the straight...Remarks in this and other publications recently about the malfunctions of totalisators at various Canterbury clubs, recalls the alleged 'good old days' of early trotting when the totalisator often commanded more newspaper space than the results of the races.

Malfunctions in the totes of those days were almost always of human interference with any errors very much intended. Nearly every racecourse riot in the 1880s and 90s involved some totalisator fraud and it is perhaps not surprising legal measures were necessary to convince the betting public that the machine had an advantage over the bookmakers. Bookmakers did not figure very strongly in early trotting for the trotting clubs were almost always insolvent or near to it, and they desperately needed the tote percentage they got. From the bookies they got very little and for their part the bookmakers soon lost interest in trying to predict the result of some trotting races.

Unfortunately some of the early clubs were inclined to let their financial embarrassment convince them that a little fraud on the public was really in the best interests of trotting, and at one stage things got so bad that trotting was in danger of losing it's appeal. Some of these clubs were themselves fraudulent, for though they had an elected list of officers much like today, these men often had no say in the running of the club at all and one prominent Christchurch club was said in the 1890s to consist of three directors who did quite nicely out of the day's sport.

The blatant attempts to make money from the public's pocket is quite well documented. The most commomn method of making sure those 'in the know' got their money was to leave the tote open long after the race had started and sometimes not long before it finished. This was because the trotters in those days were animals of very unpredictable gait and even if one was 'set up' to win it could easily ruin it's chances during the race. So the tote remained open until as long as possible for 'late' investments. The public soon caught on to this and contemporary reports indicate that the crowd near the windows often increased at closing time as punters tried to find out which horses the 'insiders' were going for.

Another trick of the tote operators (they were privately operated then) was to alter dividends during the race. The owners and their friends would place their bets on the likely winner as the horses went to the post which drastically cut the win dividend in the event of an outsider winning. At an Epsom meeting in 1895, there was a very blatant fraud along these lines. An outsider was showing £75 on the win at the start, £50 after the first lap and £25 when it ultimately won. The public though were sick of this sort of thing and they started a demonstration - some of the wiser ones having stayed and watched the tote instead of the race. The tote owner was angry that anyone in his employ should be defrauding the public and called for an inquiry. He lost some of his indignation when it was discovered that the extra tickets were held in his name. All was not lost however, for the inquiry conducted by the club was chaired by the tote propietor's brother-in-law who unaccountably found there was no case to answer. There was another riot at Epsom just before the First World War over similar goings on.

The press was enraged also at a Canterbury meeting held about the same time. There were seven horses in the race and so widespread was the knowledge of who had been 'selected' to win, that no tickets were purchased on five of the runners. 'A palpably got up thing' snorted one paper and called for the banning of some trotting clubs from operating. There is no doubt that some of these clubs were doing nothing at all for the sport.

One problem was that the totes were very primitive and wide open for any 'funny business'. Some of the early ones marked up the number of tickets held on any horse in chalk and more than one operator was caught 'adjusting' the number after the race to cut his losses. A campaign by the press in the 1890s weeded out many of the bad elements who were destroying trotting by tote frauds and the like. They called for better starting arrangements (any connection between some drivers setting off and the starter calling 'go' was very tenuous), closing the totes at the correct time, reforming clubs along proper lines and cessation of the apparently common practice of drivers taking out their frustrations by whipping each other rather than the horses.

Big money was being involved in totes at this time and in 1891 the turnover for trotting was over $160,000.

The formation of the Trotting Conference in 1896 was the turning point for the confidence men though from time to time sharp practices continued. One which was often used concerned off-course betting. In those days money from off the course could be telegraphed to the tote. This was often well informed money and the punters concerned had to be careful that tote owners didn't promptly back the horse with bookmakers off the course. One trick known to have worked was for one of the punters group to go to the local post office an hour before the off-course money came through and give the telegragh operator dozens of bogus telegrams to go to various destinations. This kept the operator busy over the period when tote agents were desperately trying to get through to the bookmakers. It also prevented other money coming from off the course.

Another rather blatant 'rip off' known to have operated in Canterbury was for the club to have races which were restricted to horses belonging only to members. These provided a real windfall, for not only could the dividend be 'influenced' by the fact that the 'insiders' knew which would win, but also the advertised stake money was pure fiction, the money in these races being 'donated' to the club - in other words they didn't pay out.

It doesn't pay to be too harsh on some of the early trotting men for some of these little tricks arose originally from the need to finance the clubs. They didn't see that they were achieving the reverse of what they intended by alienating many of the public. Certainly these days in trotting we don't have the cheeky frauds of the olden days. The only thing is that if our indicator boards don't start showing prices which are more realistic we may once again see an angry public.

Credit: David McCarthy writing in NZ Trotguide 1Jul76

YEAR: 1897

The committee of the Lancaster Park Amateur Trotting Club met yesterday, and made final arrangements for the club's spring meeting. A letter was read from Mr Spencer Vincent, offering a silver cup to be presented to the winner of the Limit Handicap. Tho offer was accepted. It was decided to license bookmakers at six guineas per day, provided not less than twenty-five paid the license fee. It was resolved to offer as an inducement towards good trotting, ten guineas as an extra prize to any horse which may break any of the New Zealand records. Mr W. A. Goodwin was appointed to work the totalisator at the meeting, and tenders were invited for a band. The usual afternoon tea will be provided for the ladies.

Credit: Star 28 October

YEAR: 1905

|

| Andrew Rattray |

The following appreciation of Mr A Rattray was written by Mr H E Goggin and is reproduced here unabridged:-

Mr Andrew Innes Rattray, who died in August 1941, in his 87th year, was aptly called the "Father of Trotting". The energy, time and thought he put into the sport was amazing. In many walks of life men are found who are unique in a particular way. Just such a man was the late Mr Rattray in regard to trotting. He was a unque character.

I joined him in August 1904, as a lad of 14, he having had only one previous assistant who started 18 months earlier. The clubs had just moved their office from Duncan's Buildings - now known as Church House - to new offices in Tonks Norton's Buildings, Hereford Street, Christchurch. Mr Rattray rode a bicycle and one of my first remembrances was of it having been stolen from outside the office and being sold to a dealer, and of Mr Rattray going for the dealer for its recovery. He eventually got it back, but never rode it again.

Mr Rattray was born in Scotland and came to New Zealand at an early age. He always had a keen partiality for horseflesh, and his trips from Avonside to West Christchurch School and back were made in a dog cart, and many a race he had on the roadside with other embryo sportsmen. Later on he owned the trotters Cleveland and Bloxwich, and won races with them at Heathcote.

His first position was to represent Matheson's Agency, a big firm of merchants and woolbrokers. Subsequently, for 10 years, he was a member of the Bank of New Zealand staff, rising to take charge of the Bills Department. The commercial education he received there stood to him in later years. After leaving the bank in 1887 he took over the secretaryship of the Lower Heathcote Racing Club, a position that had previously been held by Messrs Scott and Bamford. At that time nominations and acceptances were taken at the Empire Hotel, and the totalisator met with such strong opposition from bookmakers that £500 ($1,000) was considered a good day's turnover. This club later became a trotting club and closed down in 1893.

The Canterbury Trotting Club, which raced on the Show-grounds was formed in 1888, and Mr Rattray was appointed secretary and joint handicapper with Mr H Piper. Subsequently this club merged with the NZ Metropolitan Trotting Club. Besides the NZMTC, Canterbury Park Trotting Club and New Brighton Trotting Club, Mr Rattray was also secretary of the Christchurch Racing Club, which raced three days a year on the CPTC's course at Sockburn, and ran six galloping and two trotting events. This Club was abolished by the Racing Commission of 1910.

Mr Rattray was also the first secretary of the New Zealand Trotting Association, which was formed in 1888, and did great service in framing the rules and stamping out ringing-in, which was prevalent in those days. He often told me that on many occasions he travelled to Lyttelton by a 5am goods train to inspect horses arriving and departing. So persevering was he in trying to stamp out ringing-in that the wrongdoers soon came to the conclusion that the game was not worth the candle. The Association was also active in investigating the affairs of clubs run by proprietary interests, of which there were a number.

Up to the early 90's there was a dead set against what was then known as "the poor man's sport," emanating chiefly from racing club officials. This enmity, combined with early mismanagement, was solid hinderance to trotting, and those controlling the clubs had a keen uphill fight for many years. Their first great effort was to obtain Government recognition of the NZTA, and it was mainly due to the efforts of Messrs Rattray, Mace and McIlraith, that this was brought about in 1891.

Another matter of which he saw the evil was the danger of the sport being overdone. Prior to 1891 unlimited totalisator permits could be obtained, and through his agency a rule was passed whereby no club could hold more than four meetings in one season. The abolition of bookmakers from racecourses was another matter for which he fought hard. I have seen the racecourse detective take a man into the secretary's office on the course and a scuffle take place as he was searched for evidence of betting, which, if found, always led to prosecution. Because of Mr Rattray's desire to clear the courses of bookmakers, the local trotting clubs were more insistent upon prosecuting them than racing clubs throughout the country. After a lot of hard fighting for many years the present regulations regarding bookmakers were framed. Telegraphing of betting to racecourses, which was in vogue for many years, was another matter he fought against, he being strongly of the opinion that betting should be confined to the racecourse.

He worked hard and put boundless energy into getting the horses out on to the track. He realised that the public would not start to bet until they had seen the horses, and in those days the clubs required all the finance they could get. He frequently went to the saddling paddock and spoke sharply to the clerk of the course for not having them out, and even went around the horse-boxes urging the drivers to hurry into the bircage. Mr Rattray carried on with this work until shortly after the Great War, when the meetings had grown to such proportions that he asked to be relieved of it, and the late Mr J C Clarkson was appointed birdcage steward for the NZMTC. After working hard to bring about these reforms it was natural he should express strong views on them in later years in order to maintain them.

Mr Rattray did not always confine himself to secretarial work. In addition, he did handicapping for several years, and at odd times acted as timekepper and starter. I well remember as a youth assisting him to start at a Canterbury Park meeting at Sockburn, when the starter, Mr H Reynolds, was unable to attend, my job being, at a signal from him, to pull out the lever to set the starting clock in motion.

An incident which I vividly recall, happened during the running of a meeting by the Christchurch Racing Club. The third race had just been run when the news arrived of the death of King Edward VII. The stewards met and decided to abandon the meeting out of respect to such a great sportsman. The outside crowd and others from inside then swarmed into the secretary's office and demanded the return of their three and six pence (35c) entrance money (many had only paid 1/- (10c)). I can see Mr Rattray now, stretching himself up behind the small table, which was his desk, and defying the menacing crowd and telling them they would not get it. It was necessary to wait some time before we could leave the course with our cash.

Mr Rattray had tremendous faith in the future of trotting and backed it up in every way. At one stage, when the Addington grounds were being laid out the club had spent all their available cash and had not sufficient to pay the men working there. For some time this was paid by Mr Rattray himself, who visited the grounds every Saturday afternoon for that purpose. On another occasion, when he wanted a job done better than the committee intended to do it, because of lack of funds, he offered, anonymously, a loan of the necessary amount, free of interest, and this was accepted.

He was an indefatigable worker. Hours meant nothing to him. Originally nominations and acceptances closed at 11pm. This was altered to 10pm about the time I joined him, and the day for taking nominations was always Saturday. When the big alterations took place at the course in 1910 he spent hours there with Mr Syd Luttrel superintending them, and also with Mr Alf Luttrell in the office going through plans, etc.

I think one of his greatest virtues was his loyalty. He was intensly loyal to his clubs, and was always out to create such a standard for them in dignity and prestige that anything which did not measure up 100% in his opinion was scorned. Again, he was always loyal to his staff, particularly those who played the game. I remember an incident some years ago where a steward of one of the clubs had come without his ticket and the gateman refused to pass him in. An infuriated official then demanded of Mr Rattray that the gateman be sacked. The reply he got was "that man is carrying out his instructions; if he goes, I go."

When I went into camp in World War I, he told me he would not allow anyone to replace me, and for the three years I was away he carried on alone - an action I deeply appreciated. He was a stern disciplinarian, but beneath his brusqueness was a kindly heart and a geniality which won him great respect. His memory will live for a long time.

Credit: Pillars of Harness Horsedom: Karl Scott

YEAR: 1907

TOTALISATOR ESTABLISHMENT.

Interesting reference to the operation of the totalisator on NZ courses is made by the Royal Commission on Gaming and Racing as follows:-

At that time (1881) portable totalisators had already apparently been in use for a year or two at various race meetings. They were of a crude and elementary character and their efficiency must have been of a low order. However, the operation of the totalisator, inefficient and inadequate as it was, must have interfered to some substantial extent with the business of bookmakers operating on the same course, or the bookmakers must have foreseen in the totalisator a strong future competitor, for various attempts were made to have the totalisator ostracised.

The opponents of the totalisator were constituted of two, what might be thought, incompatable factions - bookmakers who were seeking a momopoly of gambling, and the churches and all those elements of the community which were opposed to gambling in any shape or form.

Despite this incongruity, a similar alliance in future is not beyond the limits of possibility, particularly if the lessons of experience are disregarded by those to whom gambling is abhorrent. The high watermark of the attack on the totalisator came in 1896 when the second reading of the Bill to abolish the totalisator was carried in the House of Representatives. The Bill was carried by a fair majority, but it never reached a third reading.

Over the next ten years the conflict was continued without either side gaining any recognisable advantage. Just how divided popular opinion was is shown by the fact that in 1907 the then Premier, Sir Joseph Ward, laid on the table of the House of Representatives a table showing the number of petitioners for and against the totalisator. The table showed that there were 36,311 signatures in favour of the totalisator and 36,471 against it.

Apparently prior to 1907 the interests of the bookmakers had been suffering some retrogression. Although their activities, except in a few particular rspects, were nowhere prohibited by Statute, they had been gradually expelled from racecourses by the action, probably co-ordinated, of individual racing clubs. Their activities were only limited in that betting houses were prohibited by the Act of 1881, whilst the laying of totalisator odds and dealing in totalisator tickets had been prohibited by the Gaming and Lotteries Amendment Act, 1894.

In this state of affairs, the Gaming and Lotteries Amendment Act, 1907, was introduced into the House of Representatives as a Government measure by Sir Joseph Ward. The whole measure seems to have been contentious to the uttermost degrees. The opposition to it disclosed another example, despite the divergent ultimate objects which they sought to achieve, of an alliance between bookmakers and those opposed to gambling.

From the reports of the debate on the Bill, it would seem that all members of the House were of the opinion that gambling had become unruly prevalent throughout the country. Even those who approved of betting on races were disposed to concur in some action having a general tendancy acceptable to those opposed to gambling in any form. From this limited concurrence of view and despite the essential conflict of opinion which existed between various factions, a conviction seems to have developed that it was in the public interest that all betting on races should be confined exclusively to racecourses. This conviction concurs with the views expressed by the House of Lords Committee in 1902, but seems to have been reached independently in NZ.

Credit: NZ Trotting Calendar 12May48

YEAR: 1908

1908 NEW ZEALAND TROTTING CUP

Bookmakers had two terms of legal betting in New Zealand. In the early days they were licensed by the clubs, which worked with or without totalisator betting. By the turn of the century bookmakers had been banned, but in 1908 they were back, operating on the course only, at the whim of the clubs. The situation lasted until 1911, when they were finally denied access to the courses. The 1908 Gaming Act also prohibited the publication of totalisator dividends. This prohibition was not lifted until 1950, when the Totalisator Agency Board was established and off-course betting was legalised.

The Metropolitan Club issued a large number of bookmakers' licences in 1908 and they operated in the public and members enclosures. Their operations affected first-day turnover, which dropped to £10,606, compared with £13,168 on the first day of the 1907 carnival. On the second day, 24 bookmakers operated, providing the club with £480 in fees, and on the third day 30 bookmakers took out licences. On Cup Day, despite the bookmakers, a record £18,404 was handled by the totalisator. The three-day total of £41,432 was a drop of £1209 from the previous year.

At his third attempt, Durbar, owned by Harry Nicoll and trained by Andy Pringle, a combination of owner, trainer and driver that was to become a familiar sight at Addington, won a grand contest.

On the first day, Addington patrons had their first opportunity in the new seasonto see the very good four-year-old Wildwood Junior. Bill Kerr's star easily beat 14 others, most of them Cup contenders, in the Courtenay Handicap. Dick Fly was second and St Simon third. Wildwood Junior did not have a Cup run.

A small field of nine faced the starter in the New Zealand Cup. Advance, the early favourite, went amiss and was withdrawn from the carnival. Albertorious was the favourite again, after his eight-length win in the Christchurch Handicap the day before the Cup. But Albertorious, driven by Jim August, was last all the way. He was bracketed with Fusee, driven by Newton Price. Fusee fared worse. His sulky broke just after the start and he was pulled up.

Florin took an early lead and led until the last lap, when Terra Nova took control from Dick Fly, Master Poole, Lord Elmo and Durbar. Pringle sent Durbar after the leaders and he won by two lengths to Terra Nova, with eight lengths to Lord Elmo. At considerable intervals came Dick Fly and Master Poole, with the others well beaten. Durbar's time of 4:36 was just outside Ribbonwood's national record. The stake for the Cup was raised to 500 sovereigns, and for the first of many times the qualifying mark was tightened, on this occasion to 4:48.

Most of the Cup horses lined up again in ther seventh race, the Provincial Handicap, where Lord Elmo improved on his third placing in the Cup. He gave Wildwood Junior a two-second start and beat him by eight lengths. Durbar, also off two seconds was third.

Durbar was a 12-year-old Australian-bred gelding by Vancleve. Terra Nova was by Young Irvington and Lord Elmo was by Rothschild. All three sires were outstandingly successful. A tough old campaigner, Durbar raced until he was an 18-year-old, and unsuccessfully contested the 1909 and 1910 Cups. He was the top stake-earner in 1908-09, with £682. For the fifth consecutive season, John Buckland was top owner, his horses winnnig a record £1391.

In 1881 John Kerr, of Nelson, and Robert Wilkin, of Christchurch, had imported some American stock, which laid the foundation for harness racing breeding in this country. Among Kerr's stock was Irvington, and among Wilkin's importations was Vancleve, who stayed only a short whilein New Zealand and did not serve any mares before being sold to a trotting enthusiast in Sydney. He became one of the most successful sires identified with the Australian and New Zealand breeding scenes. Apart from the great trotter Fritz, and Durbar, he sired Quincey (Dominion Handicap), and a number of other top performers who were brought from Australia to win races in this country. More than 60 individual winners of hundreds of races on New Zealand tracks were sired by Vancleve, a remarkable record for a horse who spent his stud life in Australia. Vancleve mares also found their way into New Zealand studs, the most celebrated being Vanquish - granddam of the immortal Worthy Queen, who created a miler record for trotters of 2:03.6 at Addington in 1934.

Irvington was used for only a few seasons in New Zealand before he too, went to Australia. Irvington was a poor foaler. He sired only two winners - Lady Ashley and Young Irvington - and it is through the latter that the name survived. Bred in 1886 by Tom Free at New Brighton, Young Irvington was a good racehorse, not only the first "pacer" seen on Canterbury tracks, but also a natural or free-legged pacer, racing without straps. Young Irvington left about 60 winners, and his daughters were also outstanding producers at stud. Early on they produced Ribbonwood (Dolly), Our Thorpe (Lady Thorpe) and Admiral Wood (D.I.C.).

Durbar's owner, Harry Nicoll, who raced both thoroughbreds and standardbreds, was also a breeder and top administrator. For many years he was president of the Ashburton Trotting and Racing Clubs. He retired from the presidency of the New Zealand Trooting Conference in 1947, after holding that office for an uninterrupted period of 25 years. He owned his first horse in 1902 then, in 1905, Andy Pringle became Nicoll's private trainer and they started a long and successful association. Pringle was an astute horseman, often sought by other owners and trainers to drive their horses. He was top reinsman in 1914-15 and again in 1916-17 and 1917-18. His son, Jack Pringle, was also a top horseman, winning the trainers' and drivers' premierships in 1950-51. Nicoll was top owner in 1910-11 (£1547 10s), 1911-12 (£1222), 1912-13 (£987 10s) and 1920-21 (£4161). His Ashburton stud, named Durbar Lodge after his first Cup winner, produced some great pacers and trotters, with Indianapolis, Wrackler, Seas Gift and Bronze Eagle foremost. All were bred by Wrack, who was bought by Nicoll from American owners.

Credit: Bernie Wood writing in The Cup

YEAR: 1911

|

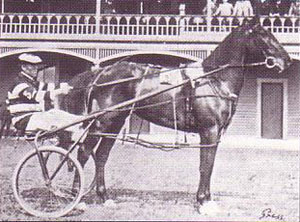

| Lady Clare and driver Jack Brankin |

Lady Clare, the second mare to win the New Zealand Cup, was a six-year-old by Prince Imperial from Clare, who was by Lincoln Yet, the sire of Monte Carlo.

Her trainer, James Tasker, who had been successful with Marian in 1907, took the drive behind her more favoured bracketmate Aberfeldy, and entrusted the drive behind Lady Clare to Jack Brankin. The Cup field was not a strong one, with Wildwood Junior out of the way. Also missing from nominations was King Cole, the star of the August meeting. King Cole, winner of the King George Handicap from Bribery and Dick Fly, and the National Cup from Havoc and Bright, had been temporarily retired to stud. The club received 14 nominations, but the early favourite, St Swithin, was injured and withdrawn. Sal Tasker, who had not raced for four years, and Manderene were two other defections. The front starter, Imperial Polly, received five seconds from the back marker, Bright. Al Franz, because of some outstanding trials, was race favourite, with the bracketed pair of Dick Fly and Redchild, from the stable of Manny Edwards, also well supported. Redchild was the only trotter entered.

The field did not get away at the first attempt because Free Holmes, the driver of Bribery, jumped the start. Medallion stood on the mark and took no place in the race, while Bribery went only one lap and then pulled up lame. Lady Clare led from the start and at the halfway stage was still in front, followed by Al Franz, Dick Fly, Imperial Polly, Aberfeldy, Havoc and Redchild. The mare held on to the lead to win by a length, in 4:38, from Dick Fly, with necks to Al Franz and Redchild. Then came Aberfeldy, Bright and Havoc.

The Cup victory was the last of Lady Clare's seven career wins, but she showed her durability by racing over eight seasons. Indirectly, she featured again in the Cup in 1988, when Luxury Liner turned the clock back 77 years. Lady Clare was the firth dam of Luxury Liner. Lady Clare's £700 from the Cup stake of 1000 sovereigns was the only money she won during the season. Emmeline, an outstanding mare by Rothschild from Imperialism, a Prince Imperial mare, won £949 and was the season's top earner. Rothschild and Prince Imperial were both still standing at stud in the Canterbury area. Rothschild was at Durbar Lodge, in Ashburton, available at a fee of 10 guineas. Prince Imperial and his son, Advance, stood at James McDonnell's Seafield Road farm, also in Ashburton. Prince Imperial's fee was also set at 10 guineas, but Advance was available at half that rate. Franz, the sire of Al Franz (third in the Cup), stood at Claude Piper's stud at Upper Riccarton, at 10 guineas. Franz was a full-brother to Fritz, by Vancleve from Fraulein.

A new surname at that time, but a very familiar on now, Dan Nyhan, introduced another great harness racing family to Addington. Nyhan trained at Hutt Park and ha won the 1909 Auckland Cup with Havoc. He was the father of Don Nyhan, later to train the winners of three New Zealand Cups with his legendary pair of Johnny Globe and Lordship, and grandfather of Denis Nyhan, who drove Lordship (twice) and trained and drove Robalan to win the Cup.

Of all the stallions in Canterbury, Wildwood Junior commanded the biggest fee, 12 guineas, but he held that honour only until 1914, when Robert McMillan, an expatriate American horseman, stood his American imports Nelson Bingen and Brent Locanda at fees of 15 guineas at his Santa Rosa stud at Halswell. He also had Harold Dillon and Petereta on his property. Harold Dillon, sire of the champion Author Dillon, was the top sire for six seasons, from 1916-17 until 1921-22, while Petereta gained some fame by siring the double New Zealand Cup winner Reta Reter.

The outstanding feature of the 1911 Cup meeting was the introduction of races restricted to trotters, particularly the Dominion Handicap. The move, prompted by the Metropolitan Club, came at an appropriate time to save horses of this gait from extinction in New Zealand racing. In the 1880s and 1890s there were two trotters for every pacer in New Zealand, but by 1911 the reverse ratio applied. With the advent of the sulky and harness from the United States, trainer in the 1890s found pacers easier to gait and easier to train, and learned that they came to speed in less time, so many trotters were converted to the pacing gait. Generally, the trotter could not match the pacer on the track.

Coiner won the Middleton Handicap on the first day, in saddle, and raced over two miles in 4:52. Quincey, who had been successful against the pacers on several occasions, got up in the last stride to dead-heat with Clive in the Dominion Handicap, with Muricata, a promising five-year-old, third. Muricata became the dam of double New Zealand Cup winner Ahuriri. The Dominion Handicap carried a stake of 235 sovereigns and was raced in harness for 5:05 class performers. Quincey's time was 4:37.4 slightly faster than Lady Clare recorded in the Cup on the Tuesday. Another of the 13 trotters in this race was the Australian-bred Verax, who started in the New Zealand Cup six times.

The meeting ended with some high-class racing on Show Day. In the Enfield Handicap, in saddle, Aberfeldy, from scratch, beat 14 rivals in 2:12.6, a New Zealand race-winning record for one mile. St Swithin, who had to miss the Cup, won the Christchurch Handicap from Emmeline and Little Tib. The Andy Pringle-trained pacer confirmed how unfortunate it was for his connections that injury denied him a Cup start.

Further improvements had been made at Addington, with a large new 10-shilling totalisator housebeing used for the first time. With bookmakers outlawed, the totalisator turned over a record £27,418 on Cup Day, and betting on the Cup of £6096 10s was a single-race record. The total for the three days of the carnival of £68,329 was an increase of £17,440 over the previous year.

Credit: Bernie Wood writing in The Cup

YEAR: 1972

|

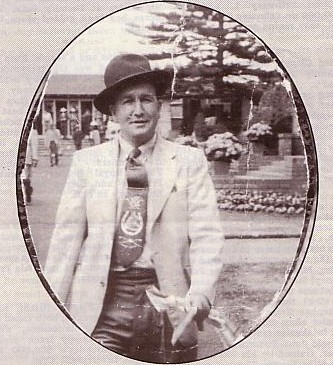

| James Bryce Jnr |

The end of what was once a beautiful romance with trotting for the long-renowned Bryce family finally came (it would seem) when last Tuesday, the day of the 1972 running of the NZ Trotting Cup - a race whose history the Bryces played an outstanding part in - James Bryce, jun. died in Christchurch aged 70.

The father and sons triumvirate of James (Scotty) Bryce and Andy and Jim Jnr really hogged NZ's trotting limelight almost right from the time Scotty, in his mid-30s in 1913, shipped out to NZ with his family and continued his remarkable career as a trotting trainer. It is said that Scotty was so good with horses that the Scottish bookmakers were delighted to see him leave his homeland. And it took no time at all for Scotty in NZ to show why.

This was despite atrocious luck at the start of the Bryce family's venture; and the story can be taken up when the little man from Glasgow stood on the Wellington wharf on a dull, cheerless morning in 1913 with his wife, his belongings and five children clustered around him, and had to take on the chin a blow that would have flattened anyone but the strongest. In surroundings where he knew no-one, wondering what the future would hold. Scotty was approached by a stranger. "Are you Mr Bryce?" And hearing the raw Gaelic accent: "Yes? Well,I have had some bad news for you. Your two horses have been ship-wrecked and are still in England." The day must then have seemed really dismal to the little man from Glasgow. Hardly a promising start in a new land. But Scotty was a real horseman - one of the world's best - and he was about to prove it in no uncertain terms.

Stakes were small and bookmakers big in the halcyon days when Scotty Bryce learned to drive imported American horses in trotting races in Glasgow; but he was a canny Scot who soon earned a reputation for reliability in getting horses first past the post. Reading some NZ newspapers from London Bryce saw the pictures of the race crowds, which decided him to come and try his luck here. When he left Scotland, he was given a great send off. Owners and trainers presented him with a purse of 100 guineas in gold. Here is Scotty's own quote on that farewell, recorded in the Auckland Star in the mid 1940s by C G Shaw: "I have never tasted liquor in my life. I thought port wine was a tea-total drink. I never remember leaving the place."

Fares and freight for the family and the horses left Bryce with £300 when he landed in Wellington, and it was at this stage that he learned that his two mares he was shipping out, Our Aggie and Jennie Lind, had gone aground in the Mersey on an old troop transport, the Westmeath, and were still in England. Subsequently, they were transhipped to the Nairnshire and after a rough passage arrived in NZ strapped to the deck after the mate had suggested putting them overboard. The mares reached here two months after the Bryce family, who had decided to go to Christchurch. The family was taken to a boarding house in the city but left after Mrs Bryce had discovered the woman of the house drank 'phonic', which is the Gaelic for methylated spirits. They went to Lancaster Park and there they settled.

Three months after reaching NZ, Our Aggie, driven by Scotty Bryce, won her first race - but she did not get it. She had not been sighted by the judge as she finished on the outside, and his verdict went to a mare called Cute whose driver said after the race: "I did not win but I could not tell the judge that." Our Aggie was placed second and the crowd staged a riot. Our Aggie won seven races in NZ and became the dam of Red Shadow, considered by Scotty to be his best performed horse ever. Red Shadow won the Great Northern Derby in 1930 and the NZ Cup and Metropolitan Free-For-All in 1933, taking all four principal races at Addington. He sired Golden Shadow winner of the 1943 Great Northern Derby, and Shadow Maid, who won the Auckland Cup in the same year.

When they first arrived with their dad and the rest of the family, James Jnr was 13 and Andrew 11. James Jnr, to begin with, got a brief grounding with the thoroughbreds, being introduced to a famed galloping trainer George Cutts at Riccarton. Before he could go far in his role as a racing apprentice, however, increasing weight forced young Jim out of the thoroughbred sport without him riding a winner. But he had been quick to learn and had what it took, Jim, who got his trotting driver's ticket when he was 15, quickly showed when he won at each of his first three rides in saddle events for the standardbreds.

Scotty had two horses engaged in a race, but the owner of one of them, the favourite, would not allow the trainer to put James Jnr up on that horse (as Jimmy had been promised) and a bitterly disappointed lad took his seat on a little mare called Soda. This happened again on another horse, whose owner, with a magnificent gesture, presented the boy with a cigarette holder and 2s 6d. However, to this Scotty added a £5 note. Finally, the first owner who had been so reluctant to avail himself of James Jnr's services asked him to take the ride, and history records that the young boy this time prevailed on the horse he had twice earlier beaten - for three wins out of three in saddle races.

It speaks volumes for Scotty Bryce's reputation that the biggest dividend paid by a horse driven by him was £14. Way back in 1923 horses driven by the old master earned over £100,000 in stakes. Scotty retired from driving when compulsorily retired aged 69 and died 20 years later. He had topped the trainers' list eight times from 1915/16 to 1923/24, being headed out in that period only by Free Holmes in 1922/23. As a driver, Scotty took the premiership five times, while Jim Jnr. was to top it in 1935/36.

In 1925 Jim and Andy were entrusted by their dad to take Great Hope and Taraire to Perth for the first edition of the Australasian Championship, the forerunner of the Inter-Dominion Championships. Both horses fared well, but on the eve of the Grand Final, the father of West Australian trotting, J P Stratton, came to the brothers and candidly informed them that Great Hope, the weaker stayer of the pair, would have to win the final if the boys were to take the championship on points. Andy, driving Taraire, got behind Jim driving Great Hope in the race, amazing horsemanship being displayed by both brothers, literally pushed Great Hope to the line to take the honours. Scotty, knowing what the lads were like, tied up the money from those successes, and Andy and Jim, needing cash, decided to trade Taraire for an Australian horse and some cash when the carnival was over.

To his mortification, Scotty Bryce not only failed to win a race with Planet, the horse got in trade for Taraire by his sons, but when he himself returned to Perth the following year with Sir John McKenxie's Great Bingen, he was beaten in the final by none other than his former stable member, Taraire. Episodes like this and the one in which Great Bingen, swimming in the Perth river, got away, swam to the bank, made his way though the city and back to his stable unscathed were part and parcel of the Bryce saga.

At his model Oakhampton set-up in Hornby near Christchurch, with it's lavish appointments that included a swimming pool for his horses, Scotty and his sons lorded over the trotting world for many happy years. Between them they were associated with six NZ Cup winners and 10 Auckland Cup winners - either in training or as drivers while they won every other big race there was to win in NZ.

Scotty trained the NZ Cup winners Cathedral Chimes(1916), Great Hope(1923), Ahuriri(1925 and 1926), Kohara(1927) and Red Shadow(1933). Of these he drove Cathedral Chimes and Ahuriri (twice) and Red Shadow, while Jimmy Jnr. drove Great Hope and Andy handled Kohara. Scotty prepared the Auckland Cup winner Cathedral Chimes(1915), Man o' War(1920 & 1921), Ahuriri(1927), and Shadow Maid(1943). Of these he drove Cathedral Chimes, Man o' War the first time and Ahuriri while Andy drove Man o' War the second time and Jimmy Junr. Shadow Maid. Then Andy for owner Ted Parkes and trainer Lauder McMahon won the Auckland Cup in 1928 & 1929 with Gold Jacket, while Jimmy Jnr. drove Sea Born to win for Charlie Johnston in 1945 and Captain Sandy for Jock Bain to score in 1948 and 1949.

Their individual victories are far too many to enumerate, but while Andy was associated with such stars as Man o' War, Kohara, Gold Jacket and, in later years, Jewel Derby and Tobacco Road, James Jnr. took the limelight with Shadow Maid, Sea Born and that mighty pacer Captain Sandy.

Eighteen months ago, Andy, at 66, was admitted to hospital with hernia trouble, told his daughter "I'm in the starter's hands," and died peacefully. James Jnr. left to join up with the other two sides of the redoubtable triangle early this week. Among the grandsons of Scotty, Colin(son of Jim) and Jim(son of Andy) were involved for a time in trotting but both gave the practical side, at least, away. It would seem the Bryce saga is over. But, who knows? Perhaps there will be a great-grandson to kindle the flame again. I wouldn't be surprised.

Credit: Ron Bisman writing in NZ Trotting 18Nov72

YEAR: 1990

|

Merv Dean, who died at his home in Auckland just before Christmas aged 67 after a long illness, will long be remembered as the man who bought the great Cardigan Bay from the Todd brothers of Mataura. But there was much more to Merv than just that.

Merv's parents ran tobacconists in Hamilton, and in his youth Merv assisted his uncle, Henry Lee, one of New Zealand's most notorious bookmakers. Lee operated a shoe shop at Frankton, but, it is said, sold no shoes. At one point in his colourful career he completely booked out the Duke of Marlborough Hotel at Russell and staged there an unofficial convention of New Zealand bookies.

Merv moved to Auckland, where he became a billards and snooker hall proprietor. Armed with a wide knowledge of racing and its ramifications, he also became a keen student of breeding, an ardent admirer of good horses and good racing, both standardbred and thoroughbred, and an aspiring owner. It could truthfully be said that he fashioned himself into possibly New Zealand's most successful professional punter. Those closest to him, considered Merv's judgement second to none when it came to horse racing.

Merv at times punted on a level to match the late Max Harvey, but, in direct contrast to that leviathon gambler, Merv shunned publicity and throughout his life maintained a very low profile. He never asked for a privilege to go on to a racecourse. He paid his way in, and never went onto a grandstand, preferring to go to the rail, as close as he could get to the horses that he loved to bet on. At Alexandra Park, scene of 11 of Cardigan Bay's 80 wins, including two Auckland Cups, Merv's favourite vantage point was on the rail at the two-mile start in the old Derby area, where he would buy a pie and rub sholders with the workers.

Merv with his Mother raced the good pacing mare Ruth Again in the mid-1950s. The daughter of Dillon Hall was trained for them for four wins as a four-year-old by Roy Purdon (then at Te Awamutu), and later in life won them a race from Morry Holmes' Riccarton stable and another when trained at Pukekohe by Colin Hadfield.

Rapt in the progeny of the imported American stallion Hal Tryax, Merv bought from the Todd brothers in 1961 a gelding by that sire named Motif. After this pacer had won at 40-to-1 at Claudelands in March 1961, he handed him to Peter Wolfenden, from whose Auckland stable Motif was to win four more races. Boosted by a good betting win, Merv soon after bought from the Todd brothers (for £2000 and two £250 contingencies) another Hal Tryax gelding, who, as Cardigan Bay, had won two of eight three-year-old starts and three of four starts at four.

Registered in the name of Merv's wife Audrey, Cardigan Bay under Wolfenden became a champion, his numerous wins including the Auckland Cups in 1961 and 1963, the NZ Cup in 1963 and the Inter-Dominion Grand Final in Adelaide the same year. Cardigan Bay went on to further fame and fortune in America, where under Stanley Dancer, he became, as a 12-year-old in 1968, the world's first pacer to win a million dollars.

One of Merv Dean's best thoroughbreds in New Zealand was Town Guard. At one stage of his career this good galloper was disappointing, and Merv's suggestion to his trainer was to jump him over hurdles in the centre of Pukekohe. His reasoning was that slipping and sliding on the heavy clover in the infield would teach the horse to run better on the flat. His theory was borne out when Town Guard immediately won the Stars Travel Gold Cup at Tauranga, beating Lampada. Merv then sent Town Guard to Victoria and successfully punted him to win a hurdle race in Melbourne. Brought back to Baggy Hillis' Takanini stable, Town Guard was one of the early favourites for a Great Northern Hurdles when he broke down on the eve of the race.

One of Merv's closest friends, current Auckland Trotting Club president Cliff Koefoed, labels him "the greatest judge of horseflesh I have known...He had something like 70 horses, and only one failed to win a race," he said. Koefoed added: "Very tough in business, he was generous to a fault to down-and-outers. When he learned that the guy who assisted him in the billard room at Onehunga had five kids and a Morris Minor, he and Audrey gave the guy an open cheque to buy a decent car for his family."

Koeford recalls accompanying Merv on whirlwind forays to Christchurch, Wellington and even Australia for assaults on the tote and bookmakers that were usually successful. "On a Trentham trip we put £200 on Mali Peter in the first leg of the double, and when he won we put the lot all-up on Golden Defoe," continued Koefoed. "They were £1 tickets, and had to be exchanged into five shilling units. They were still punching tickets for us after the second leg horse had won. We got £2500 each. We rang our wives, Irene and Audrey, and got them to book a table and meet us that night at the "Gourmet" in Auckland, I think it was the first time Merv had ever been into a top-class restaurant to have a meal."

Merv Dean is survived by Audrey.

Credit: HRWeekly 9Jan91

| << PREVIOUS | 1 2 | NEXT >> |