| THE BEGINNINGS |

YEAR: 1913

INVENTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE TOTALISATOR

From time immemorial racing and betting have been a way of life for a large proportion of the world's peoples. When they built the pyramids maybe the gang bosses held a lottery on the day's progress. Cock-fighting in Eastern countries generated a betting mania, and still does. The charioteer raced for the prize, and his lady's favour, but I guess he had a few drachmas on the side with his rivals. The Eskimo bet on the size of the fish he'd pull out of the ice-hole; and "having a little on the dogs" is a favourite pastime in many countries.

In New Zealand early in 1840 the military garrison at Auckland held the first race meeting. Wellington was next in 1841, celebrating the founding of the settlement with theirs. Each succeeding province had a meeting at it's first festival: Canterbury's was held in 1851. That was still the era of colourful bookmakers who had been calling their odds for nearly 200 years.

But betting on horse racing in this century has had more impact on a larger number of people the world over than any betting ever before. It is all due to that machine called a "totalisator" which the Concise Oxford Dictionary describes as "a device showing numbers and amount of bets staked on a race with a view to dividing the total among bettors on the winner." It sounds so simple.

As I stood watching the complicated machinery of the modern totalisator it seemed a far cry from one I had seen in the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland. I wanted to find the story of the origin of that one, and of the years between it and the infernal machine that takes my dollars now and sometimes gives me back a few.

The story unfolded as I searched files and publications, and plucked the brains of knowledgeable men. They took me to see the bowels of the robot, and my brain reeled at the intricacy of it all. One of the steel cases housed enormous ropes of electrical wiring - the nerve centre servicing the ticket machines and the aggregating machines and whatever. It seemed a vulnerable spot. They told me it was continuously inspected; even a mouse could cause an error of $1000. Rows of electric batteries can take over if the national grid fails; and a diesel plant stands by.

It became a fascinating study, and I was filled with admiration for the two New Zealanders who built on a Frenchman's system, and was responsible for the wonderful device we have today to bring us wealth or woe if we are susceptible to its charms. Mr Oller was a Parisian businessman, and as a side-line to his selling of toilet articles he conducted lotteries and a bookmaking business. On the latter he consistently lost money. At last he devised a system which would allow people to bet among themselves, and give the winner a part of all the money bet, in proportion to the individual wager. I had wondered what the "Pari-mutuel" was. This is it. "Parier" means to wager, and "mutuel" is between ourselves.

So, in 1872 Mr Oller in an office in Paris prepared many stacks of tickets, sold them and used his system for race meetings near the city. It was in demand, and he extended it by sending carriages and an army of clerks and accountants to sell pari-mutuel tickets on the courses themselves; in Belguim and England as well as in France. His commission was between 10 and 20%, and his profit enormous with the popularity of the betting system. It was completely honest; he was an honest man, which was not always the case with some bookmakers. New gambling laws put him out of business for some years; but by 1890 he was in business again though paying a government tax. His division of the pool money has altered little since then.

Queer-looking betting contrivances were used on race tracks before this, and the "marble" machine was used in Australia. When a ticket seller issued a ticket he dropped a marble into a chute for that selected horse. It rolled down to a counting place at the end of the buildings, and the dividend was arrived at by the number of marbles at the end of the winners chute. This simple system failed when few marbles got past a dead, undiscovered rodent body halfway along the chute.

Then a New Zealander named Ekberg became interested in Oller's pari-mutuel betting, and produced a hand operated machine which would speed up the procedure of selling tickets and recording bets. He called it a totalisator, and it was first used in 1880 at a race meeting of the Canterbury Jockey Club and in the same year at Auckland's Ellerslie race course.

Though still crude, other improved machines followed, but all were manually operated, and subject to fraudulent manipulation, and without any governmental restriction in their use. Then early in this century came the great revolution in racing circles. George Julius, the son of the Bishop of Chrischurch and Primate of New Zealand (himself no mean artificer) began his professional career as assistant engineer to the West Australian Railways Department. He had graduated from the Engineering School of Canterbury College in 1896.

He became chief draughtsman and engineer in charge of tests; all tests I presumed, for his report on "The Physical Characteristics of Australian Hardwood" (it would be used for sleepers) is still a standard work of reference. He married the daughter of the engineer in chief of West Australia: wise man, she would be brought up speaking the same language. Her christian names, I thought strange and beautiful: Droughsia Odierna, though she had Eva for an everyday one.

About that time irregular voting was suspected in the Australian elections, and Julius invented a foolproof vote-counting machine for the Government. It was rejected however, but he was not dismayed and decided it could be adapted as a totalisator. The family moved to Sydney in 1907, and in his garden workshop, it took him five years to perfect an automatic totalisator which would make racecourse wagering safe and accurate.

By 1912 it was finished, and George Julius was a triumphant man when the managers of Ellerslie racecourse agreed to buy and install his invention. He wished it to be called the "Premier" and he, himself supervised the erection of every section, and the screwing of every nut and bolt.

On a Staurday in June, 1913, the first automatic totalisator in the world came into operation and was a colossal success. For the first time the horse racing public saw a machine that automatically and instantaneously recorded and showed the number of tickets sold on each horse, and the aggregate number of tickets sold right throughout the progress of the betting.

Julius saw a world market for his Premier; so back in Sydney he set up a proper workshop and went into business. In spite of the great cost all of the leading courses in Australia brought his totalisators, New Zealand showing the way. He and his leading technicians went overseas to promote them, and he installed them on courses in England, France and India, beginning what was to be a great international enterprise.

It seems strange that a man with no interest in racing should have given this thing to the racing world. But his totalisator was his sideline, for as a consulting engineer he began the firm of Julius, Poole and Gibson, and was the senior partner until his death in 1946. His numerous contributions to science, his professoinal and administrative genius and his chairmanship of the mighty Council of Scientific and Industrial Research from its inception, were recognised in 1929 when he was created a Knight Bachelor.

As markets grew the totalisator was manufactured by a company calling itself Automatic Totalisators, and improvements were continually added to it. In 1932 Julius, a director of the company, added an automatic odds-computing device; and by a system of electrical impulses the modern ticket machine prints an transmits the amount of the investment as it is made, to the adding mechanism, and simultaneously issues a ticket. The company still produces the greater part of betting equipment for the world's race tracks, whether it be for galloping or trotting or dog racing. In New Zealand the law prevents totalisator betting on dog racing; but the Auckland Greyhound Racing Club has recently requested he Internal Affairs Department and the New Zealand Racing Authority to grant it a permit for its spring meeting this year.

Each installation is custom built to suit each particular set of problems and situations. When the company receives an order, an army of experts, acting on replies to a dozen questions sets to work on a study involving design, architecture, mechanical and electrical engineering and whatever, before submitting the plan to the client. All equipment is built as a series of small units and tested and packed as they are finished then shipped to their destination. Experts arrive by air and install them on the racecourse whereever it may be. The factory can never show a finished article. They will tell you "there's no use looking here for anything. You should go and see the new one we've just installed in Caracus in Venezuela." Or it may be Longchamps in France, of Sweded or Brazil.

The engineers say they have the best job in the world: a pleasant trip to a faraway place with a happy round of racing thrown in. For when you visit a race track in any part of the world the chances are that you will place your bets on a Julius Premier Totalisator. Other big manufacturing companies operate throughout the world, but are smaller. Through one of them, the English Bell Punch and Printing Company, another name came into the picture. Henry Strauss, an American, improved on the Julius machine by applying the principle of the automatic dial telephone to further speed up the operation and cope with any betting load placed on it. The New Zealand branch of that company was joined with Automatic Totalisators in 1964 and the enlarged firm manufactures most of the macines here and in Australia.

The first Tote-mobile, a small totalisator mounted in a caravan-trailer, was in use after the war. This proved of great value to clubs that could not afford the more costly equipment. It is a familiar picture on our nice country race tracks. From that time on improvements to installations came thick and fast, until now totalisators are in the electronic computer age, and betting on the totalisator is big business. Even at an ordinary Addington race day close to $750,000 pass through the totalisator om combined on and off course betting, and 80% of that is from the dollar punter.

In New Zealand, churches and bookmakers opposed the totalisators for entirely opposite reasons, and a bill to abolish them passed the second reading in Parliament, but not the third. And in 1910, by an amendment to the Gaming Act, bookmakers were excluded from racecourses, and the totalisator became the only legal means of betting in New Zealand. Today the Totalisator Agency Board is the only legal off-course betting; the electonic computer equipment is being considered for its offices. In 1918 the first inspector of totalisators was appointed by the Government, with provision for the position to be a permanent one.

Racecourse management the world over, to have a profitable business, is always concerned with the number of patrons it could attract to, and keep at the course, and various innovations are used to freshen up popularity. For years dividends were paid only on a win, then win and place equipment was installed. Then the doubles and quinella systems were introduced.

In America the doubles originally operated on the first race of the programme to get patrons on the course early; the quinella was for the last race, so holding patrons as long as possible, with consequent length of betting time. These purposes have long since outlived their usefulness.

I wondered how the name ("quinella") came into racing, and they told me it originated in Mexico after the conquest by the Spaniards in the sixteenth century, when they adopted an Indian court game. To establish the champion in their "Jai-Alia," a game similar to squash but with woven baskets instead of rackets, six of the best players entered a contest, by lot each player being numbered one to six. The loser of the first two contestants is replaced by number three, and this sequence continues until five winning points are established. The same applies to produce four winning points.

As betting on horse racing developed in Mexico patrons demanded that they should be able to bet on the first two horses past the post as with Jai-Alai players. Now this betting system operates on the modern totalisator, investments are fed into a punched tape recorder and read by an electronic instrument.

Stil more sophisticated machines will no doubt appear for a more sophisticated form of betting but the four men Oller, Ekberg, Julius and Strauss are, with their experts responsible for the development of so many devices to improve the operation of pari-mutuel betting, that their names will never be forgotten. And racing men to say that pari-mutuel betting removed the crooked race track bookmaker and that the totalisator made pari-mutuel betting honest.

But in spite of it all, the calculators (and they are human) with great rapidity (one of them could add four columns simultaneously), still have to work out the dividend. So when you receive your payout give a thought to the human brain that as yet must take an active part in this end result of its genius, the totalisator.

Credit: Phyllis Kerr

YEAR: 1913

The first automatic totalisator was devised by George Julius, son of the Archbishop of New Zealand. His machine was installed at Ellerslie

YEAR: 1949

|

Mr Harry Reynolds of Redcliffs, a well-known breeder, trainer-driver and administrator of trotting in Christchurch died recently at the age of 86. He was connected with sport for more than 60 years, and he also invented one of the first automatic totalisators and produced the first pneumatically-tyred sulky. Starting barriers used by some clubs in Canterbury were also invented by Mr Reynolds.

Mr Reynolds was a watchmaker by trade. His health failed in 1893, and he was ordered to take up an outside occupation. He bought a mare for £12/5/- and renamed her Sapphire, and she turned out to be the greatest trotter of the day, at one stage winning nine races in succession.

Mr Reynolds was a member of the committee which formed the New Brighton Trotting Club. He was a life member of three racing clubs in Canterbury. In 1890 Mr Reynolds invented a starting clock and was appointed a starter. This prevented him from racing horse but he was one of the nine men invited by the late Mr H Mace to his home, Brooklyn Lodge, North Brighton where the New Brighton Trotting Club was formed. Mr Reynolds later resigned as starter and took up the position of timekeeper.

Credit: NZ Trotting Calendar 20Jul49

YEAR: 1977

|

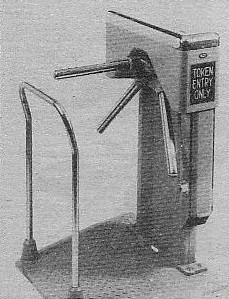

A new type of automatic turnstile, new to NZ at least, may soon be in operation on trotting and racing tracks in this country.

First developed in Australia by Automatic Totalisators Ltd, the automatic turnstile is now in widespread use throughout Australia, not only on racing and trotting tracks but at other major sporting venues. The automatic turnstile does away with the need for clubs to employ large numbers of gate staff to collect entrance money, and the model pictured was tested by the NZ Metropolitan TC at its two night National meeting this month.

Available either as permanent fixtures or as portable turnstiles, they offer great scope for racing and trotting clubs to save on costs. The turnstiles can operate either by patrons placing the entrance money directly into the coin block, or where admittance charges vary, by the use of tokens which can be purchased on the way in. The token system is the most commonly used on Australian trotting tracks where many New Zealanders are already familiar with the system.

At a time when all NZ trotting clubs are looking at ways of cutting costs, this new turnstile seems to offer wide scope for achieving this aim, particularly if clubs in the same areas were to get together to obtain the equipment in partnership.

First developed in 1959, the equipment has proved most successful and beneficial to clubs in Australia and it does not seem it will be long before NZ clubs adopt the same system.

Credit: NZ Trotting Calendar 30Aug77

YEAR: 1985

|

Travel has always been a big interest for Pat Venning, the senior Totalisator Agency Board manager for the northern region of the South Island (on-course division), and his retirement from the position this week will allow more time to do just that. Pat and his wife Judith plan to travel to the United States, United Kingdom and Europe next year, but recently purchased a camper-van for their more immediate travel plans in NZ.

A Londoner by birth, Pat came to NZ in March, 1949. "I had been travelling around during the war and afterwards I could not settle at home, so I thought I would come out here," he said.

He worked as a Post Office technician before the war and for a short time afterwards, but took a job farming when he first arrived in NZ. He worked on a sheep farm in Central Otago for a time but a strong interest in athletics took him to Auckland in 1950 for the Empire Games. A keen runner who favoured 880 yard and mile events, but also enjoyed cross country, Pat competed at club level in the United Kingdom and ran for St Paul's Harriers in Otago when he worked there. Although he attended the Empire games as a spectator, he did get to run against some of the athletes who had competed in the Games when they toured NZ after the Games. "I did reasonably well," Pat said, "but I didn't win."

After the Empire Games visit to Auckland, Pat returned to the South Island and took a job with the Post Office in Invercargill, but because of his "English experience" he was soon transferred back to Auckland where he continued to work for the Post Office for some time before accepting a position with Control Systems NZ, on-course totalisator operators, in November, 1951. That was the beginning of what has been a long career working within the racing industry in totalisator administration.

Before joining Control Systems, Pat had only a minor interest in racing. "It was the technical side of the job which appealed to me," he said. He had attended a few race meetings in England, but had not been in NZ. "I went to the Derby meeting which most people in London seem to go to. Everything more or less stops," he added.

Back in the early 1950s most NZ racecourses apart from some metropolitan tracks, used a manual ticket system. The tickets were pre-stamped but racehorse numbers were handwritten on as the bets were taken. However, automatic totalisators were operating on a larger scale in Australia at this time and it wasn't long before an Australian opportunist - Mr J A McKay - decided to bring the NZ racing industry into the age of automation. He formed his own company here, Control Systems NZ, which used the imported English manufactured Bell Punch electro-mechanical equipment. Control Systems NZ was later taken over by the English totalisator manfacturing firm Bell Punch, who renamed the company Bell Punch NZ. But Bell Punch were manufacturers of totalisator equipment rather than operators and in 1965 they sold out to Automatic Totalisators, a Sydney-based company who changed the name "Bell Punch NZ" to Automatic Totalisators Ltd.

ATL went through until 1981, by which time they were the main on-course totalisator operators in NZ. But by this time racing and trotting clubs had given an undertaking to participate in a new computerised on-course totalisator system. The expensive new technology involved in the venture was beyond any one on-course totalisator operating company and only a few of the large metropolitan clubs had the financial strength to face up to the expensive future. So the TAB was asked to develop and operate the new computerised system on behalf of the clubs. The takeover was in July, 1981, and most racing, trotting and greyhound clubs in NZ now use TAB facilities on-course. Since the takeover there has been a gradual conversion away from the old electro-mechanical equipment, on-course, to the new computerised equipment. Last year saw the final operation of the electro-mechanical system purchased by the TAB from ATL in 1981.

Pat was South Island manager for ATL and, later on, also for the TAB prior to the introduction of the on-course computer equipment. When the new computer equipment was introduced, the TAB split New Zealand into regions for servicing arrangements and Pat was then appointed senior manager - northern region - for the South Island. His new appointment covered racemeetings in the Nelson to Waitaki area. He saw his job, on raceday, as that of "a general overseer," managing staff, handling customers queries and making sure everthing ran smoothly. "Everthing is monitored through a control van," Pat said. "We manage the staff on the day and are responsible for their work, but we don't pay their wages," Pat said.

The TAB also trained operators to use the new computerised equipment, and every operator was given the chance to participate in the retraining programme. "There was no age bar," Pat said. "All operators were put through the training programme." Some had found the new equipment more difficult to adjust to than others, but at the end of the programme that was not a consideration. If they made it through the course they retained their job. The new technology had meant big changes for punters and operators but, from a managerial position, Pat said that he had not found the computerised system difficult to adjust to. "You are still dealing with the public just the same," he said. "Selling is different. Operators are on their machines all day." Before the introduction of the computerised equipment, operators had "closed down" between races and "cashed up" each time. This meant operators were able to talk to one another during races. But under the new system this did not happen. "They don't cash up until the end of the day," Pat said. He felt that much of the "friendly atmosphere" encouraged by the old system had been lost since the introduction of computerised equipment. The new equipment was "right up to world standards" and had given on-course punters a much more streamlined service. "It is a speedier operation which saves people queuing up. Now they can do everything at one window," he added.

About three years after joining Control Systems, in Auckland, Pat was transferred back to the South Island when Bell Punch, his English employers, sent him to Christchurch to set up a South Island base for their company. He has remained in Christchurch since then and during more than 23 years of work within the totalisator administration and control, Pat has seen many changes in both on and off-course betting. But, putting aside the introduction of computerised equipment, the subsequent arrival of Jetbet and the major impact that has had, perhaps the most obvious change has been the modernisation and acceptance of on and off-course betting. The often dingy, back-street betting shops hidden away from the public gaze have apparently gone for good, replaced by bright, modern main street offices designed to attract attention and encourage new customers. The new swept-up image was a result of a change in public attitudes, Pat felt. People are becoming more liberal in their thinking. Things that were not discussed several years ago were talked about today. "It is just a question of public acceptance," Pat said.

Considering his work, Pat said he had "No regrets. I have had a very interesting time over the years and met a lot of nice interesting people. All the totalisator staff have been a good crowd to work with and it has been like one big happy family over the years."

Credit: Shelley Caldwell writing in NZ Trot Calendar 23Apr85